Extra Cover

Published in Extra Cover

2035 — A World Turned on Its Head

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of the United Nations is the go-to global source of information on the pace of climate change and the scientific basis that frames its impacts on contemporary societies. The IPCC scientific report of 2023 has concluded that each of the four past decades has been successively hotter than any other preceding decade since 1850. Another unequivocal finding is that global mean temperatures at surface level have risen by 1°C (compared to the 1850-1900 reference period) because of human activity.

The report has also indicated, based on different scenarios for future emissions, including mass net increases and/or dramatic decreases in greenhouse gas emissions, that global surface temperatures will rise throughout the 21st century, pointing out a greater than 50% likelihood that the 1.5°C threshold will be met or surpassed between 2021 and 2040. I propose, therefore, that we consider a set of dynamics from 2035 onward. And brace for impact.

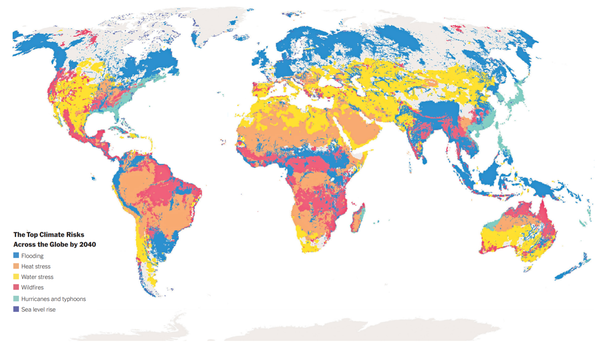

The climate will have warmed up over 1.5°C, the lowest threshold agreed upon by countries under the Paris Agreement of 2015. Climate change significantly undermines human security on numerous axes: economic, political, social, and environmental. The breadth of present risk is in no way surprising. Over decades, scientists have issued warnings of more frequent, longer and more intense heat waves; of increasing rise of ocean levels; more torrential rain; stronger storms; change in the distribution of pests, blights and pathogens; ocean warming and acidification; hotter, longer-lasting forest fires and more protracted drought periods.

Meanwhile, political decision-makers have underestimated the scale of such dangers, the speed at which they would emerge, and consequent, cascading social disruption. All of this became alarmingly clear during the global food security crisis of 2032, brought out by the overwhelming impact of El Niño, which affected the rice basins in Vietnam and China, among other countries in the region.

The crisis accelerated political action to cut down on greenhouse gas emissions, although the global energy transition from fossil fuels to renewable sources was already underway, driven by the increasingly lower cost of renewable energy and improvements made to storage technology. It came as no surprise that risk capital investors, asset managers and financial oversight bodies were the first to spot the impact of climate changes on market behaviour. In the mid-2020s, they began to redirect their investment toward clean energy and more resilient assets, to the detriment of fossil fuels and infrastructure under threat from climate change. Currently, many countries are indeed reaping the rewards of the energy transition, although others have not been able to adapt at a sufficiently rapid pace — some out of inaction, others because over-reliance on fossil fuels underpinned their national economies, and others were wholly subordinated to the ends of war, like Russia. As a consequence, not only did their geopolitical sphere of influence dwindle, but so did their income, which led to cuts in domestic investment, weakening an already brittle welfare system and fanning the flames of growing public unrest.

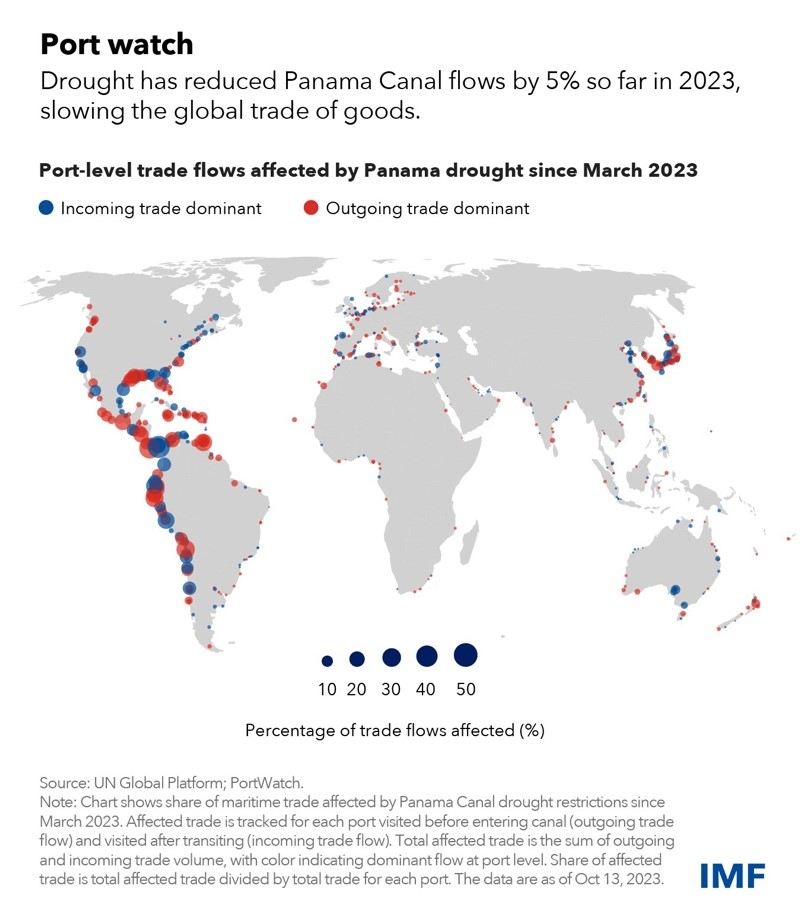

Climate change also caused massive disruption to world trade over the prior decade. Energy transition reduced trade in fossil fuels and increased demand for new energy products, such as hydrogen, batteries, and green steel. Climate change disrupted supply chains, markets, infrastructure and, of course, consumers’ purchasing power. Most world trade still relies on shipping lanes and seaport infrastructure, but rising ocean levels and more intense storms has led to harbour shutdowns that sometimes go on for months.

Less developed countries have borne the brunt of climate change. A lack of capacity and ineffective government response to natural disasters have fed into public discontent around growing inequality, corruption, low-quality public service and frail political institutions. Both governments and their detractors now use online disinformation to pursue their agendas, which often leads to more polarization, sustained by narratives as emotional as they are fallacious.

Unsurprisingly, separatist movements, terrorism, and organized crime have flourished in less developed nations, as non-state actors rush to fill the voids where governments have retreated. It was surprising, however, how quickly those very actors built a solid regional and global network, wholly distinct from the preceding, atomized stage where they competed among themselves. The efficacy of the Southeast Asia terrorist attacks in 2033 revealed how much more in sync those groups are now, operating a the transnational level with better coordination, less hindered by internal competition, benefiting financially and organizationally from the political, economic and psychological impact of their actions.

Amidst all of this, it still mattered that allies outside the region kept channelling support and humanitarian aid when large-scale natural disasters took place. Less encouraging, however, is the fact that volatility in those places created opportunities for major world powers to intervene and compete among themselves. The early 2035 incident on the South China Sea, the fourth one in under a decade, demonstrated how strategic competition, opportunism, online disinformation and errors in calculation can contribute to military confrontation and undermine efforts to lower the temperature. None of this bodes well for the coming decade.

The past few years have once again confirmed that the Indo-Pacific region, where over half the world population resides, packed into dense, claustrophobic cities, is highly exposed to climate risk and others. In Indonesia, for one, the ocean has been lapping up the shore at a rate unseen over past decades. The extreme yet sporadic floods of 2020 have become an annual event across large sections of the country, regularly displacing a sizable portion of Indonesia’s 310 million citizens. Forced internal migration aggravated by many from outside joining the tens of millions of displaced, people from all the Asian southeast seeking refuge in other countries. The previous year, an island nation on the Pacific moved its entire population to Australia for exclusively climate-related motives of grave import.

Much of southern and southeastern Asia is highly vulnerable to gargantuan phenomena like El Niño, nourished by the intensity of humid years, increasing the risk of cyclone events, and by the lengthy dry years. The region finds itself at a critically precarious juncture: new cyclones have grown stronger, causing unprecedented floods in places still recovering from extreme heat, drought, and systemic shock from the food security of the previous year as well as the devastating crisis of 2032. Outside humanitarian aid is less effective, hindered by new weather-related obstacles that give rise to extreme heat and devastating fires in the Western US, southern Canada, most of Europe, and Siberia. The same kinds of obstacles, the ones scientists have long ago linked to climate change, are simultaneously affecting sub-tropical monsoons in South Asia, causing severe flooding in parts of the sub-region that might otherwise have escaped the disruptions caused by El Niño.

Over the past two decades, regional institutions and organizations like ASEAN, the Pacific Islands Forum, and multilateral development banks have ramped up their efforts to address many economic, political, security, and humanitarian challenges brought about by global warming. Across the Pacific, they’ve been key to resettle island communities displaced by ocean level rise and stronger cyclones. However, their efforts lag behind the magnitude of climate risks and connected large-scale impacts. Difficulties increase when they need to drive regional approaches to widespread crisis, as a few nation-states choose to put up walls and turn inward instead.

It is however encouraging that most countries, along with regional and multilateral organizations, along with the private sector, have agreed on a 2036 global summit that should breathe new life into multilateral efforts that could deal with these multifaceted challenges. The IPCC’s latest report suggests that swift transition to renewable energy and recent, more ambitious political measures may keep warming under 2.5°C, lessening the risk of crossing yet another dangerous climate threshold.

This is a prospective scenario, based on worsening trends, analytical insights grounded in data accepted by the scientific community and severe enough that we should feel alarmed and call on the international community to take deliberate political action with bravery and a sense of coordination. Many other effects could be listed, but a few of the above provide more than enough motive to come up with decisions, speed up schedules, and affirm public policy that will ensure adequate transition in industrial economies in order to mitigate problems already in place while we try not to exacerbate the ones that will follow.

Planet, science, policy, citizens. These are the dots we need to connect once and for all.

Text written before November 1, 2024.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.