Extra Cover

Published in Extra Cover

Russia’s Footprint in Africa

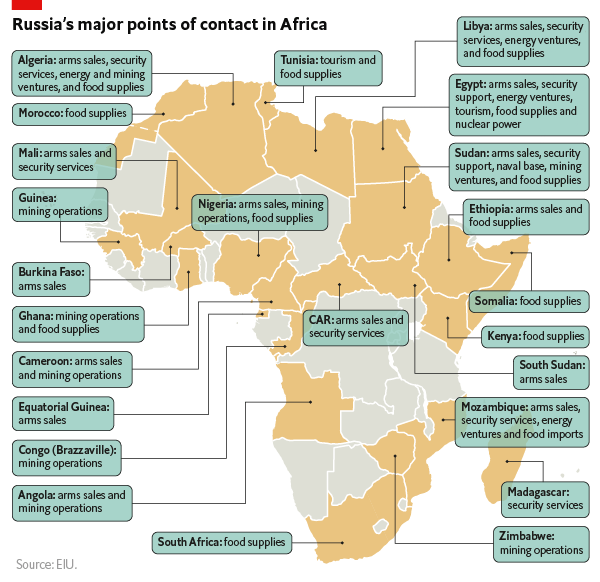

The African continent has unfortunately become the stage for Russia’s aggressive moves to impose regime attitudes that cater to the Kremlin’s designs. To that end, Putin has exploited sources of resentment against a few European countries, namely France, and sponsored coups with the Wagner group’s support, which has been operating in the Sahel for years. Despite the chances Yevgeny Prigozhin took to try and change the Russian military’s chain of command, the truth is Prigozhin’s role is too important for the Kremlin, especially in Africa.

No surprise, then, that the Wagner Group leader has made an appearance at the second Russia-Africa summit in Saint Petersburg, where 49 African countries were represented, although only 17 heads of state attended. Considering that the foregoing summit in 2019 saw 54 countries in attendance and 45 heads of state, it wouldn't be right to say that Putin enjoys massive, expressive support these days. Maybe it would be more appropriate to note that several African countries want to exploit multipolar alignments and not commit to one narrative. Much as one might say that Putin’s aggression is intended to yoke regimes to his interests by backing coups.

From an economics standpoint, Russia doesn't have actual structural relevance in Africa. It contributes less than 1% of foreign direct investment on the continent. As to trade relations, its contribution is likewise modest (14 billion dollars), compared to the value of African trade with the United States (65 million dollars), the EU (285 million dollars) and China (254 million dollars). Russia's main exports to Africa are cereals, weapons and nuclear energy. Over 80% of Russian trade with Africa concentrates on four countries: Egypt, Algiers, Morocco, and South Africa.

Russia also happens to be the lead weapons exporter to Africa, holding half the market. While Russian arms are sold to 14 African countries, Algiers, Egypt and Angola make up 94% of weapon purchases in the region. Russia also advances the building of nuclear power stations on the continent, especially in Egypt, although the lead Russian company of that sector, Rosatom, has signed cooperation deals with seventeen other African governments, including Ethiopia, Nigeria, Rwanda, and Zambia.

Concerning one of the matters of the day — cereals — Africa relies on Russia for 30% of its supply, and almost all of it (95%) is wheat. 80% of these wheat exports go to North Africa (Algiers, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia). Overall, Africa imports 65% of the wheat it consumes. This percentage should grow apace with the African population as all demographics studies point out. Given food price shock caused by the halt to supply Russia has brought about, as it refused to renew its agreement with Ukraine to export cereals over the Black Sea last July — a number of African leaders asking Putin to reconsider — maybe the key issue is to understand what strategy African countries will pursue in order to become less reliant on a single supplier in the medium term, even if signals around the short term are contradictory and let the Kremlin impose its agenda.

Russia’s central goal in Africa is to claw back influence over a strategic area from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. This explains his support to the coup led by general Abdel Fattah al-Burhan in war-torn Sudan, 2021. To that end Russia focused on Libya, where it opposed United Nations efforts to put in place a stable, unified government in Tripoli. In 2019, Russia sent Wagner Group mercenaries to help Khalifa Haftar consolidate his role as a new strongman, employing substantial military resources such as fighter planes and land-to-air missiles. Were Russia to succeed in the end, that would give Moscow a military presence in North Africa, matching alignments in Algiers and Egypt, establishing a naval presence across the Mediterranean and the Red Sea which would allow to Russia to put the brakes on global maritime transportation by controlling choke points on the Suez Canal and the Bab al-Mandeb strait between Yemen and Djibouti. Over 30% of shipping container traffic needs those two lanes.

Another of Russia’s strategic goals for Africa is to wipe out Western influence. That was recently affirmed in the Central African Republic (CAR) and Mali, where Russia has come to dominate presidential security in the CAR and the Mali military junta. In both cases, the Wagner Group has taken up the role of Praetorian Guard to the seated powers, facilitating Russian political influence and access to raw materials of key significance. To that end, the group uses extreme violence leading to a growing number of civilian casualties, much as they have done against locals in Libya, Syria, and Ukraine.

One thing is for certain: the deterioration of democracy has direct implications to African security and development. Three quarters of all conflicts in Africa, and 85% of the 36 million forcibly displaced persons on the continent come from places under authoritarian rule. Recent UN reports on the situation in West Africa and the Sahel describe 2.7 million displaced persons and 1.6 million malnourished children since inter-ethnic violence and a sequence of coups exacerbated food insecurity in a region where climate change and war threaten local subsistence, given the wave of military coups since 2020: two in Burkina Faso and Mali, one in Tchad and more recently one in Niger.

At the CAR, a Russian citizen serves as national security advisor and Wagner Group mercenaries act as a guard corps to President Faustine-Archange Touadéra. As they established themselves in the country, clustering their presence around gold and diamond mines, mercenaries became ever more hostile toward UN peacekeeping forces, which have deployed more than 15,000 men to help stabilize the country. In Mali, Russian disinformation campaigns begun in 2019 have discredited the UN, France, and the democratically elected president, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, deceased in 2022. Russia was the key supporter of the military coup that ousted him in August 2020.

Meanwhile in Burundi, Pierre Nkurunziza, elected in 2015, expanded his term limits, and the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement, which ended 12 years of civil war (1993-2005), were violated. This led to protests, met with brutal repression, leading to over a hundred casualties and hundreds of injured. Russia subsequently blocked a UN resolution in condemnation of Nkurunziza’s regime, asking for non-interference from outside actors. This was of especial significance, as it paved the way for a number of term violations in Central Africa: Joseph Kabila in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Denis Nguesso in Congo, and Paul Kagame in Rwanda. Each one of these constitutional trespasses enjoyed Russian support.

Niger has in the meantime become a key country in the region for France after the military coup of 2021 in Mali, Bamako having severed security ties with both Paris and Burkina Faso. Paris then decided to support Niger in its efforts to combat jihadi groups increasing their power in the Sahell and North Africa, which includes organizations affiliated with Al Qaeda, the African Islamic State, and Boko Haram. The recent military coup in Niger could keep France from renewing its security cooperation in Africa, although Paris, Washington and Brussels consider President Mohammed Bazoum a strategic ally, seemingly in tune with the statement issued by the extraordinary, late-July CEDEAO conference, which demands a return to pre-coup normalcy.

In a way, Russia’s modest economic footprint in Africa may not condition the Kremlin, as it can avail itself of alternatives to spread influence across the region: armament, support to military coups, disruptions to food supply, nuclear capacity-building. Given those resources, do African populations see Russia as a factor of development or, inversely, as an erosive force against stability and peace on a broad swath of the continent? It would be worthwhile to pursue deeper opinion surveys on the matter. So should we study the durability of high-level political alignments, considering the signals that came out of the latest Russian-African summit. Neither African countries’ expectations on the renewal of the Black Sea cereal export agreement nor goodwill missions to broker peace with Ukraine have resonated with Putin and his Kremlin. Once again, when they pull the rug out from under her, Russia hardens its behaviour abroad, smashing laws and spreading chaos.

Taking a broader view, Russia’s motivations for a power comeback to Africa entail advancing its geostrategic goals on the Mediterranean, NATO’s southern border, and on the Red Sea, a vital hub for international trade, thus displacing Western influence and normalizing a Russian view of the world, using Africa as means toward greater strategic ends. We will see whether this investment pays off in the long term.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.